03.01.2024 | Jochen Bettzieche | SLF News

SLF researchers have calculated that the zero-degree line around the South Pole is retreating significantly faster than the global average. This has consequences for the region's environment and biodiversity – but also economic and political implications.

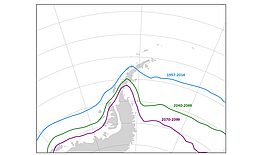

In Antarctica, climate change is progressing much faster than the global average. Sergi Gonzàlez-Herrero, a scientist at the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF), has now investigated the exact speed at which this is taking place. The atmospheric researcher has looked at how far the zero-degree isotherm around the Antarctic – a key measure of the freezing point (see box) – has shifted southwards in recent decades.

From 1957 to 2020, the average was 16.8 kilometres per decade. That compares with a global mean of 4.2 kilometres per decade. And the speed is increasing. Gonzàlez-Herrero has done the calculations for various climate scenarios. “Depending on the climate scenario, we expect a value of between 24 and 69 kilometres per decade in the coming years,” predicts the researcher, who anticipates chain reactions with negative consequences for the environment and economy.

What are… isotherms?

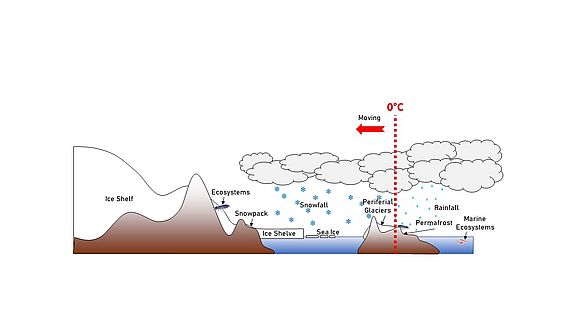

Similar to the contour lines on maps, which connect points at a fixed elevation, isotherms are lines that show places with the same temperature. Because temperatures fluctuate, they usually relate to average values over a specific period. The zero-degree isotherm latitude (ZIL) is particularly significant as it is the isotherm that shows the average position of the freezing point.

“Because the zero-degree isotherm is shifting south, the interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere are changing,” explains Gonzàlez-Herrero. The effects are even stronger on land, especially on the Antarctic Peninsula, which extends much further north than the rest of the continent. There, the researcher expects the weather phenomena to change in the future, with more rain and sleet falling instead of snow, with negative consequences for glaciers and ice sheets, for example.

Moreover, less ice on the sea will also mean the disappearance of solar protection. Because ice and the snow that accumulates on it reflect light, they act like a sunscreen for the ocean. If they disappear, the water will warm up more than before.

Danger for penguins ¶

But this is about more than just physical and meteorological processes – life and biodiversity in Antarctica are also at stake. Non-native species that are not cold-resistant could migrate to the continent, especially invertebrates. “Meanwhile, native carnivorous species such as penguins, seals and whales would have to look for new regions to live in, with the right environmental conditions and sufficient prey,” says Gonzàlez-Herrero. Penguins are under additional threat as the change to more rain and the associated mud and runoff poses a risk to their nests and chicks, thus jeopardising whole populations. The entire Antarctic ecosystem could therefore change significantly.

Consequences for politics and economy ¶

For the tourism industry, this will mean having to find alternative destinations if it wants to continue to offer trips to penguin colonies and similar attractions. However, that is a relatively minor economic impact. Gonzàlez-Herrero is more concerned that ecological change could increasingly lead to political tensions over raw materials, fishing grounds and the search for unique biomolecules. All of these will become more easily accessible as Antarctica warms up. Which it will. Faster than has previously been the case. “Just how fast depends on how much global temperatures rise as a result of climate change,” says Gonzàlez-Herrero.

Contact ¶

Links ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.