13.02.2025 | Sergi Gonzàlez-Herrero | SLF News

SLF scientist Sergi González-Herrero is conducting research in Antarctica for two months. From there, he regularly reports in Catalan for the Catalan Foundation for Research and Innovation (FCRI) to get young students aged between twelve and sixteen involved in science. The SLF also publishes his articles.

Have you ever stopped to listen to nature in the middle of the mountain just after a snowfall? You've probably noticed that everything turns quieter. That is because fresh snow is a very good absorber of noise. This phenomenon occurs due to the porosity of the snow. When snow gets old, it becomes denser and loses this property. We use this effect to our advantage because we use the sound of snow to study the blowing snow.

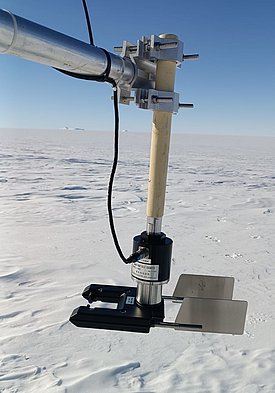

How do we do it? One of the instruments that helps us measure the blowing snow is the FLOWCAPT, an instrument similar to a neon tube but with a microphone inside. When a snowflake from the blowing snow impacts the tube, it produces a sound in it. An internal program captures the sound waves and transforms them into the amount of snow transported.

Here you can see one of the experiments I did when testing the instrument:

The second instrument we have “sees” the snow instead of “hearing” it. It's called the Snow Particle Counter (SPC). The sensor is positioned facing the wind and consists of a laser emitter and a receiver that detects changes in light intensity. When a snow particle passes through the laser beam, it partially blocks the light, allowing the receiver to measure the reduction in intensity and calculate the particle’s size. The SPC thus counts individual snow particles, determines their size, and records how many pass through per minute. We use both instruments to study cloud properties.

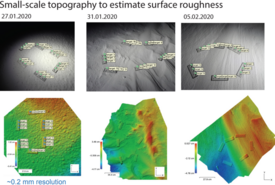

Another of the activities I do this day is photographing the snow. You may ask, why, if it is all white? Are you sure? The wind creates small roughness in the snow and causes small shadows to appear with the light. That is why it does not reflect 100% of the sunlight. This is important because snow with less reflection absorbs more of the sun's heat. To study how the roughness of the snow changes, I am taking photographs of the snow every week from different angles with drawings to identify where the photograph was taken.

With these photographs and a technique called photogrammetry we can reconstruct the surface of the snow in 3D. Here you can see an example made by my colleagues.

Taking photographs of the snow has made me pay more and more attention to it. I had never realized the number of shapes that can be seen in it. These days I have become fond of taking photographs of the relief of the Antarctic snow, not for science but for fun. Here are some examples. Maybe one day I can set up an exhibition on the shapes of the snow in Antarctica. What do you think? Do you believe it could be a success?

Snow structures from the Antarctic ¶

(Photos: Sergi Gonzàlez-Herrero/SLF)

Already published ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.