SLF researchers are studying the links between climate change, microclimate and glacier retreat. They intend to use the data to forecast the impacts on plants, animals and people in the region.

A late August evening on the Hintereisferner, a glacier in the Austrian Tyrol: small points of light dance across the ice. They come from the headlamps of a group of researchers from the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF), who are out on a rather unusual night hike. They are visiting their measuring stations, temporarily installed on the glacier, so that they can collect data at night as well as by day.

The SLF scientists are researching the microclimate on glaciers, mainly looking at how the glacier wind helps to protect the glacier itself and how the general weather conditions can disturb this microclimate. Rebecca Mott, a snow hydrologist at the SLF, explains: "We want to understand what factors influence the temporal and spatial dynamics of glacier winds and how these winds affect glacier melt. Little research has been done on this subject up to now." Temperature and air humidity also play an important role here, as does the constantly changing surface of the glacier.

"We can't save the glaciers" ¶

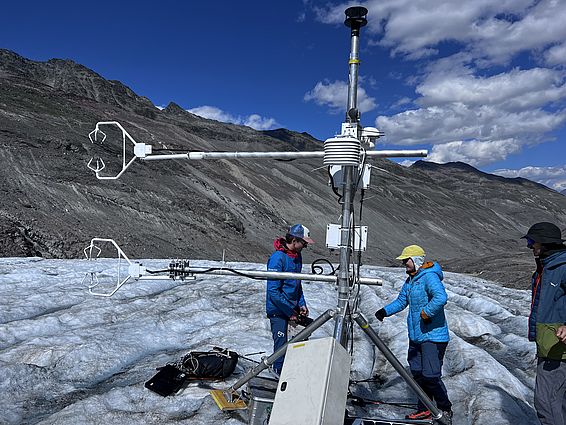

To investigate these complex relationships, researchers set up around 15 meteorological stations of different sizes on the Hintereisferner, measuring temperature and wind fields and associated turbulent exchange processes. During the intensive measurement period, they also created atmospheric profiles every three hours using probes and drones and recorded the temperature field near the glacier surface with infrared cameras in high temporal and spatial resolution.

Mott and her colleagues hope to use this data to gain a better understanding of glacier melt. "We can't save the glaciers, but with the knowledge we acquire about the glaciers' microclimate we can make more accurate predictions about when they will disappear," she explains. This is important because where ice masses are pushing downhill today, an ecosystem will spread in a few years or decades. This will deprive people in the region of a water reservoir, affecting many aspects of daily life, from electricity production and agriculture to drinking water.

A tin box accommodating 12 people ¶

This was already the second measurement campaign by SLF researchers on the Hintereisferner. Known as Hefex2 for short, it was a partnership between eight scientific institutes. They carefully planned in advance which partners would install which sensors at the 15 measuring stations.

The whole campaign spanned a period of three to four weeks. Rebecca Mott herself stayed overnight at the research station near the Hintereisferner, which is scarcely more than a tin box accommodating twelve people. Her colleagues Michael Haugeneder and Dylan Reynolds pitched their tents nearby. Some researchers even spent nights in the open air or actually on the glacier itself near one of the stations in order to take continuous measurements at night.

Temperatures in the height of summer: only 5 degrees Celsius ¶

A huge effort was involved in this work. At least once a day, the scientists walked the entire glacier to check on their equipment. This was particularly important because these weeks saw the Alps being hit by a heatwave, meaning that the glaciers were melting faster than usual. "We'd find that a measuring station worked perfectly one day but was out of position the next, or that a new stream had started flowing right through the station set-up," says Mott. Despite the heatwave, the researchers wrapped up in multiple layers of jackets and jumpers – and even then they were often frozen. This is because while the glacier wind protects the glacier from the heat, it is also cold. Even at midday in the height of summer, temperatures sometimes reached only 5 degrees Celsius.

Five hours walking time ¶

To cap it all, they also had a storm to contend with. Fortunately, most of the researchers had left the glacier a few days earlier, taking much of their equipment with them. Only a few remained on site to look after the stations until the end of the measurement campaign.

Finally, Haugeneder also returned to the glacier to dismantle the equipment and bring it safely down to the valley – a journey of around five hours over the glacier and its foreland and along a narrow mountain track. But this time in daylight.

Links ¶

Contact ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.